Alphatracks has always been aimed at Sony and Minolta SLR users. Not that there is anything wrong with non-SLR gear, There have been numerous great non-SLR cameras sold under the Sony/Minolta brands. You have to draw the line somewhere, however, and since I have primarily used SLRs, I like to stick to what I know.

I’ve noticed that many readers are somewhat unclear as to which cameras are actually SLRs. Some appear to think it means any camera that uses interchangeable lenses. (Which is not the case.) Others mistakenly apply the term to so-called “bridge” or pro-summer cameras. These cameras typically rely on an electronic view finder (EVF) , which disqualifies them as a dSLR. So what exactly makes a camera SLR?

Shouldn’t that be a MLR?

It’s the instant return mirror (and supporting system) that puts the reflex into a SLR.

Most people know that SLR stands for “single lens reflex,” which in itself is fairly confusing. After all, nearly 100 percent of the SLRs ever produced are designed with an interchangeable lens mount. Shouldn’t these cameras be called Multiple Lens Reflex cameras?

To understand just why we refer to these cameras as single lens units we need to examine a bit of camera history, The early cameras, such as those used by Matthew Bradey during the American Civil War, recorded a single image at a time. The photographer looked through the lens, focused, composed and then inserted the film plate behind the lens to make an image. While the entire process was crude by today’s standards, the photographer enjoyed great control, since he looked directly through the actual imaging lens to compose the shot.

While this was satisfactory for still life, portraits and landscapes, this process did not lend itself to rapid photography. These early cameras could only record one image at a time. Which is why you have never seen a motor-driven view camera.

Realizing the need to offer sequences of exposures, camera makers begin to experiment with various roll-film designs, With a roll of film in the camera, the photographer could fire off continuous images without reloading. While this improved throughput dramatically, it caused another problem. The roll of film had to pass closely behind the camera’s optics, which meant that the photographer could no longer look through the camera lens to design the shot.

Rangefinder cameras appear to keep things in focus

There was no problem with the lower-end consumer roll-film cameras, because these generally used an inexpensive “fixed-focus” lens. Better quality optics require the lens to be focused, however, and as we’ve seen, the photographer couldn’t look through the lens with a roll-film camera. One of the first solutions to this problem was the Rangefinder — a type of camera that offered a distance measuring scale in the viewfinder. By determining the range from the viewfinder, the photographer could then adjust the focus to match — usually with very good results.

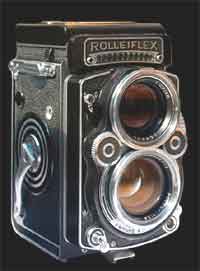

Twin Lens Reflex cameras offer another solution

Twin lens reflex used upper lens to focus, lower lens actually took the photo.

While the rangefinder type cameras worked well, the camera industry is always evolving. A second method of allowing the photographer to focus and compose appeared in the “Twin-Lens Reflex” cameras. These cameras used two identical lenses, arranged one on top of the other in the manner of an over-and-under shotgun. The film winds past the lower lens, while the photographer can focus through the upper lens. Since most of the twin-lens cameras were fairly bulky, designers added a mirror and ground glass to the top of the camera, hence the term “reflex.

Now the user could hold the camera at waist level and look down at the ground glass which previewed the image via the mirror behind the upper lens. As the user adjusted the focus on the upper lens, a gear mechanism moved the lower “taking lens” to match.

While both rangefinders and twin-lens cameras offered a credible way to focus and preview a shot, neither allowed the photographer to look directly through the imaging lens. This made exact composition difficult in certain situations.

SLRs take cameras another step forward.

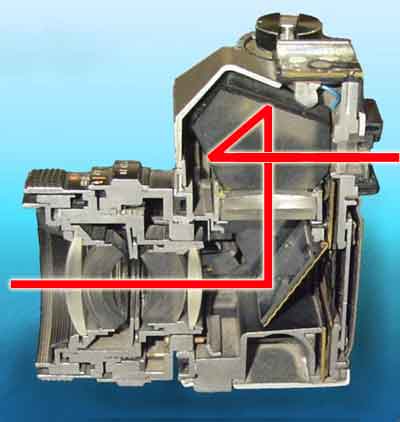

Cut-away view shows the light path through a typical SLR. Light enters through the lens, hitting the lower mirror, where it is reflected upwards. It then strikes the top of the prism, where it is reflected again to strike the front of the prism. It is reflected yet a third time to pass through the viewfinder.

In their quest to allow users to see through the actual “taking” lens, camera makers turned to the periscope — a simple device using two mirrors placed at opposite angles to bend the light path. Periscopes are easy to understand — any kid can construct one from a couple of mirrors and some scrap wood. In a camera, the lower mirror is placed at a 45 degree angle directly behind the lens. Light striking the mirror is projected upwards to a ground glass. A pentaprism, which contains two additional mirrors, is located behind the viewfinder. The prism is used to flip the image so it can be viewed “right-side up”

There is just one hitch. If you’ve been paying attention, you no-doubt realized that the lower mirror blocks the light path to the film (or digital sensor as the case may be.) Now the photographer can look though the lens, but the image can’t be projected on to the film plane.

So the camera designers had to add another wrinkle. They had to move that mirror. Just long enough to make an exposure, since when the mirror moved, the photographer couldn’t see anything through the lens. So they designed the “instant-return” mirror.

At the instant of exposure, the mirror flies upward, the shutter opens, closes and the mirror snaps back down. It is a incredible feat, when you consider that instant return mirrors have to flip up and back in a heartbeat, over and over for the life of the camera.

Once the instant return mirror was perfected, photographers could once again design their images by looking through the lens. Unlike the twin lens reflex, this new breed of camera needed only one lens to focus and shoot with. So they became known as… you guessed it…. Single-Lens Reflex cameras.

Digital SLRs work exactly the same way — the same reflex system of mirrors and prism is used in front of a a digital sensor instead of film.

For further reading:

How Stuff Works – Single Lens Reflex

Images on this page published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

SLR Cutaway derived from image provided by:

Rolleiflex Twin Lens Reflex provided by

Jean-Jacques MILAN/Photographie – 40

Technorati Tags:

History isn’t my favorite subject, but this is REALLY interesting. It’s amazing how the technology has changed over the years. It makes you wonder where we’re going next.

While I find the article interesting, my own experience of using view camers (including one late 19th century model for which I still have the lenses) is markedly different from that described in one respect; I never (to this day) have the experience of looking “through the lens” with a view camera (or TLR for that matter); rather, I find myself looking at a picture of the world, displayed on a ground glass (albeit inverted and reversed).

From my first SLR (a 1960s Nikon F1) I experience using an SLR as actually through the lens – I don’t experience it as looking at a picture on a ground glass. I experiece it as looking at “the thing itself” (to borrow a phrase from Edward Weston, even if to use it in a different sense) just as I do through my corrective glasses. Perhaps this stems from lifting the SLR to my eye and looking through it as one does with a telescope or binoculars.

In the same breath I note that I have always preferred that the ground glass in an SLR not have a range-finder-like split image or micro-prism focuser – because it distracts from that experience of “looking directly through the lens.”

Oi hai ther, I am from Soviet Russia – where the blog post writes you! So, pleez excuse my terrible English. I can’t believe the post I have just read, it was very informative. Back here in Russia, people can barely write so reading your article was like a breath of fresh air. I’d like to personally thank you for writing this post today and I hope everyone else that is reading this today got as much enjoyment out of reading it as I did. I can’t wait to check back and see what other things you write. – Warm reguards from Russia to you all in the USA! We keep in touch.

Thanks for this AWESOME article! I will definitely have to tell my friends about it!

Cheers!

what about this second sentence?